There was no shortage of issues to address when Africa’s top leaders converged for the annual African Union (AU) Summit which concluded this week in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The gathering took place at the height of multiple crises, from the toll of geopolitical problems initially linked to the pandemic, then the war in Ukraine to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, on top of the instability locally amid unconstitutional changes of governments, and threat posed by terrorism or militia groups.

The bad news is that never, since the creation of the AU, has Africa had to contend with a big number of coups d’états like has been the case lately. The AU top leadership says that failure to counter the trend has undermined the prospects of silencing the guns.

Meanwhile, the continent also grapples with persistent food insecurity and high malnutrition levels at a time effects of climate vagaries have also intensified thanks largely to unmet pledges for adaptation by industrialized nations.

The worse news, according to the AU leadership, is that member States’ support to the continental institution barely affords the latter political and financial muscle that match the scale of the problems it confronts.

Current level of member States’ support also doesn’t position the AU to efficiently deliver on a wide range of development and integration programs.

Noncompliance

Blame goes to, among other things, States’ noncompliance with decisions adopted at AU level, coupled with low funding.

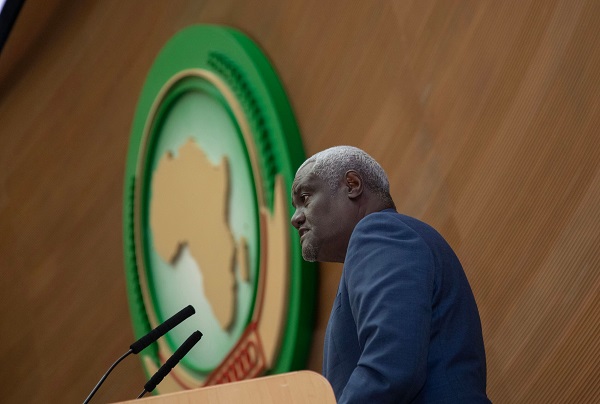

According to the AU boss Moussa Faki Mahamat, these factors conspired to make it impossible to move forward on several key continental issues, including implementation of crucial activities and programs in line with Agenda 2063.

The latter is the continental strategy which aims for an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa with people’s hopes and needs at the center.

As for the good news, the AU shared a 10-year evaluation report of its activities with details of what worked, what didn’t work and what needs to change.

The report was not made public by press time, but sources within the AU say it could help member States work out a solution to prevailing bottlenecks if they are really keen on putting the continental organisation and its organs on a good footing going forward.

Meanwhile, going by the statements of AU head Mr. Faki to both the Executive Council and the Assembly on February 14th and 17th respectively, conditions were not conducive for the continental organization to deliver on its mandate over the past decade.

For instance, 93 per cent of decisions adopted by the AU over the past three years remain on paper with no execution by member States. He did not name names, but he confirmed that the phenomenon hampers work of almost all AU organs.

A retreat between member States and the Commission, which sought to work out a solution did not find any, he said.

Decades old instruments

Mr. Faki in his address did not go into full details of decisions that are lagging behind except a mention of the Pan African Parliament (PAP) and African Medicines Agency (AMA).

But a look at the AU’s database of treaties points to several decisions and legal instruments covering a wide range of sectors pending ratification by member States. Many are enforceable only after a minimum number of countries have done ratifications. Others require ratifications by all member States to pave the way for their domestication and subsequent implementation.

In the case of the Pan African Parliament, for instance, it was established in 2004 to serve as the legislative arm of the AU based in South Africa. However, it remains without legal powers decades later.

The protocol establishing PAP was revised in 2014 and has got only 16 of least 28 ratifications that are required to enter into force.

Besides, member States adopted in 2019 the establishment of Africa Medicines Agency in response to the growing disease threats and concerns over global vaccines inequity. The AU first found the going hard garnering 15 required ratifications to set up the agency, which it achieved in 2022.

It has since struggled to get member States meet the financial and administrative cost of its physical establishment and operationalisation.

Also read: Non-ratification of AU treaties slows down Africa flagship projects’ implementation

Several continental legal instruments suffer the same fate. Many date back to between 2000 and 2016, and could be outdated by the time member States come to the same page of ratifications. Implementation of programs designed based on their provisions, too, cannot materialise.

The African Martime Transport Charter (adopted in 1994 and revised in 2010) is one of them. The African Road Safety Charter (2016) and the Free Movement of People protocol (2018) are also on the long list of legal instruments whose enforcement is held up in the prevailing ratification bottleneck.

Compliance with AU decisions, including ratifications by member States is done in a sovereign perspective. The AU can only bank on States’ political will to move forward.

Mr. Faki underlined in his address to Africa’s top leaders that “tendency to make decisions without real political will to execute them has grown to such an extent that it has become devastating to our individual and collective credibility.” Whether national authorities will heed his call remains to be seen.

Funding woes

These issues are weighing down the work of the continental organization at a time it’s equally grappling with funding woes. It is estimated that member States contribute only 9 per cent of the budget needed to carry out its activities.

This definitely means that the AU heavily relies on donor funding at 91 per cent. To analysts, this has a bearing on its independence.

Which countries are remitting their contributions and which ones are not? This information is not out in public domain yet. However, nations either embroiled in conflicts or on the sanction list make up non-contributors.

Past efforts to plug the funding woes have involved the implementation of 0.2 percent levy on imported goods within member States with effect from 2017. The decision is yet to be implemented in almost half of the countries. The funding woes leave AU offices at the headquarters and its organs across the continent poorly staffed and without budget for key activities.

Overall, these issues await the new leadership of Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, President of Mauritania who recently took over as the new Chairperson of the African Union. They will equally shape the succession conversation ahead of Moussa Faki Mahamat’s end of tenure this year.