With world’s attention to war in DR Congo slowly waning, thousands of Congolese families longing for peace and justice are left at the mercy of warring parties.

Many had hoped to see a quick end of the crisis when the Rwandan regime, long accused for fuelling the conflict, denied pursuing regime change in DR Congo, seizure of its territory or its mineral resources’ exploitation, months after signing the peace accord mediated by Washington.

M23 rebels, widely seen as the protégé of the Rwandan ruler Paul Kagame, had equally bowed to the U.S. pressure and relinquished part of conquered territories of the mineral-rich East, leading to days of calm.

However, the recent drone attack on a key airport infrastructure in Kisangani by the rebel movement has again dampened propsects of peace. The African Union condemned the attack as amounting to violation of international law, and act of terrorism.

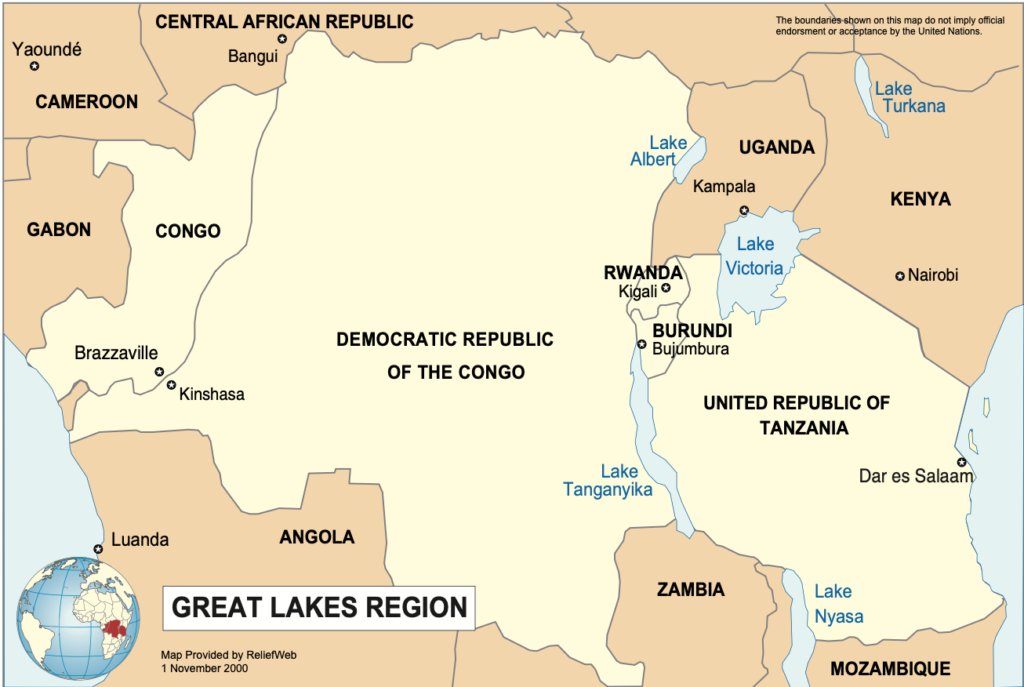

The escalation further prolongs the suffering of millions Congolese. Agonies are especially written in the faces of thousands, mostly women and children who are scattered across the region as refugees displaced by the latest and previous cycles of violence.

But beyond the destructive effects of the war, families now contend with an even bigger problem — the toll of ethnic tensions fomented by months of war propaganda with effects stretching far beyond the Congo.

Ethnic sentiments were particularly rife at the height of the war with Rwandan politicians linking fighting to the drive to stop alleged ‘slow genocide’ targeting Congolese Tutsis in East of the country.

Also read: YEAR AT WAR: Families of fallen Rwandan soldiers wait for answers

Another notion that was on display in Kigali war propaganda was one of ‘incorrectly’ drawn borders which Rwanda links to the loss to the DR Congo of a chunk of its territory in pre-colonial past. But the narrative quickly shifted when international pressure piled.

Kigali told the world that it had only mounted defensive measures to shield the nation from threats of the FDLR, a Hutu rebel group linked to the 1994 genocide present in Congo.

Too late

But it was too late. The ethnic sentiments had quickly spread into transnational ethnic networks and communities, drawing people back to identitarian cleavages to tell Hutus from Tutsis or vice versa. The two ethnic populations found in Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Eastern DR Congo hold historical ties and unresolved grievances, in instances.

In Rwanda where a Genocide against the Tutsis decimated lives of over a million people in 1994, ruler Paul Kagame and his entourage see the ethnic Hutus in the country and beyond as people that need to be kept in check, and the Tutsis as people that need to be mobilised to be vigilant and rally behind his regime for protection.

The Rwandan ruling elites resorted to this to maintain power, but the thinking hurts the drive to forge a collective national identity.

It is problematic for a nation that promised to correct mistakes of previous regimes having successfully eradicated ethnicity in official documents. Authorities had also rejected the notion of existence ethnic groups, instead referring to them as a concept invented by the colonial masters as part of their divide-and-rule system.

In practice, the Rwandan ruling elites continue to view the young generation in the prism of children of Tutsi survivors and children of Hutu perpetrators, a tag that has been normalised in national conversations and it goes on unquestioned and unchallenged.

Controversy

Authorities had also embarked on the drive to compel ethnic Hutu people without distinction to seek forgiveness for Genocide crimes as part of Ndi Umunyarwanda (I am Rwandan) campaign. The regime would later decelerate the campaign when it came under scrutiny over inflicting collective guilt on the Hutu population.

The drive had sparked controversies that the Rwandan regime was using the campaign as a political tool to justify exclusion of Hutus who refuse to pledge allegiance or show remorse, while labelling adversaries as people not worth of governing on the basis of actual or alleged role of their Hutu parents or associates in the genocide three decades ago.

The spillover of this subtle ethnic mobilisation beyond the Rwandan borders was seen causing unease among ruling elites of neighbouring countries, fuelling bad ethnic rhetoric involving politicians across the board.

Many recall the recent divisive utterances of the Congolese former military spokesperson, Major-General Sylvain Ekenge, against the Tutsi community. They were not an isolated incidence.

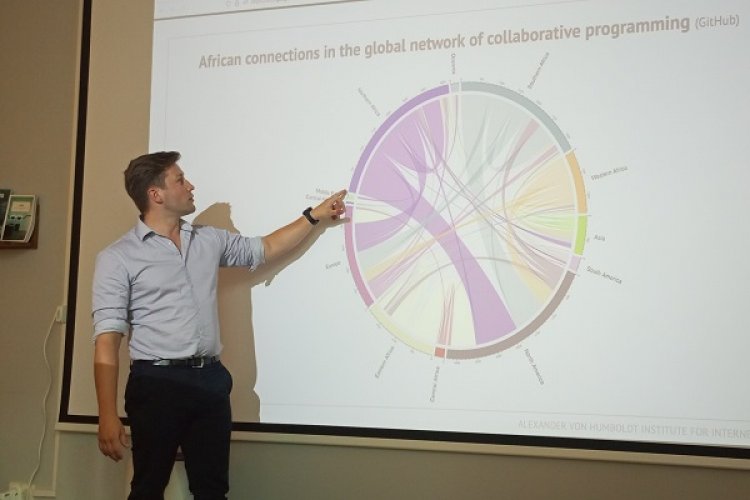

Like the Congo, media and online spaces in Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda have lately become awash with rhetoric of the same nature by national politicians targeting individuals or groups of people in the region based on their real or perceived ethnicities.