Imagine living in a world without litter, and when there is [litter] it becomes a resource. Experts concur that such a life would be well within reach if people prioritised sustainable lifestyles — where nothing goes to waste.

It’s this that paves the way for what’s popularly known as the circular economy, and the question many ask is: What does it take?

For years, humanity promoted extract-transform-use-and-throw away lifestyle when it comes to management of earth resources. This has come to hit everybody hard in form of recurrent environmental and climate vagaries expected to spell doom for future generations, if unchecked.

With the increase in industrialization, parts of the globe and Africa, in particular, have had to grapple with pollution dangers emanating from discarded waste such as plastics, hazardous industrial waste and others which pollute the soil, food, water and air, increasingly rendering parts of earth unlivable.

The mess is exacerbated by poor waste collection and inefficient disposal systems.

Also read: Plastics are in the fish you eat; Lobby groups now push for regional ban

Environmentalists are of the view that more than 80 per cent of the environmental impact emanating from human production could be addressed at products’ design stage, and the responsibility falls on companies to ensure that what they churn out are durable, reusable, easily repairable, non-toxic, and can be easily upgraded or recycled.

According to Dr. Tobias Schmitz, Environmental Advisor at 7Cbasalia Global, the company behind the Basalia technology used to turn waste into valuable products, the above is the key highlight of emerging policies in parts of the globe to support transition to circular economy.

The European Union, for instance, is moving to compel companies to report what they are doing with regard to bringing down resource consumption, waste generation, and how circular their designs are, on top of the recovery of products inside their industrial processes.

Enforcement of such obligations starts next year under the European Union Circular Economy Action Plan adopted in 2020.

“It is going to have an impact in the Africa region because many of these supply chains which are used for European processes are drawing raw materials and resources from the African continent. I think it’s worthwhile looking at these products because the production starts in Africa,” says Schmitz.

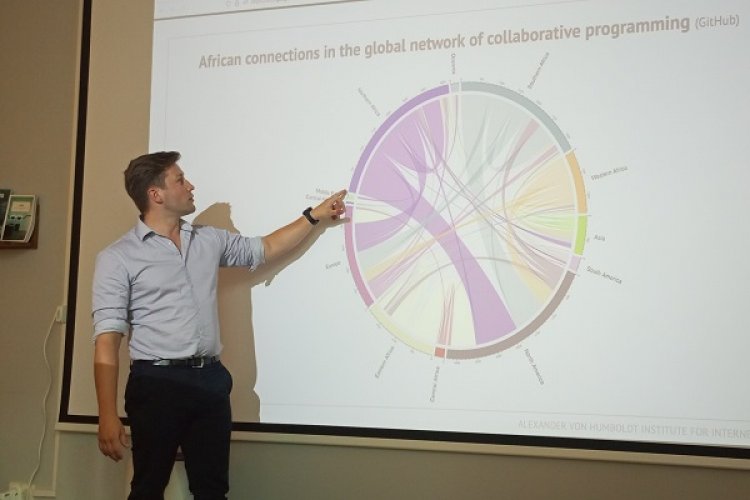

Schmitz is one of the experts who addressed journalists from East and West Africa at a workshop on circular economy held early this month in Nairobi.

Other experts who weighed in on the challenges of transitioning to circular economy include Piotr Barczak, member of African Circular Economy Network (ACEN) and Henrique Pacini, Economic Affairs Officer at UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Sustainable lifestyle

Going forward households and everyone need to come up with ways of reducing waste production, and Piotr Barczak advises people to normalise composting at household level and reusing materials as many times as possible.

“What everyone can do is try using reusable materials, try to repair or repurpose your waste. Don’t throw your jacket if it can be repaired. If your shirt is not reusable anymore you can still use it for another purpose like a cleaning material,” he said, adding that any other ways of handling waste like burning, dumping and incineration are not sustainable.

Calls on the public to embrace sustainable lifestyle grew particularly in light of concerns over plastic pollution across parts of Africa.

The continent is responsible for only 5 per cent of global plastic production, but bears a huge burden of the emissions linked to plastic pollution.

Henrique Pacini of UNCTAD says people must avoid using plastics as much as they can. Instead they could resort to plastic substitutes or plastic alternatives. The former are natural materials that have similar properties to plastics, while the latter are biodegradable plastics.

“Both are ways to contribute to reduction of plastic waste” he said.

The question, however, is — and this worries environmentalists — that increasingly plastics continue to compete with environmentally substitutes and their alternatives. Substitutes often face higher import tariffs than their plastic equivalents.

“To change this, there is need to either put in subsidies or make harmful items more expensive,” opined Pacini.

Environmentalists also advocate for tax incentives, green procurement policies and regulatory or economic instruments that promote the development and use of non-plastic substitutes if economies are to achieve circularity.

These are aspects that environmentalists expect governments across Africa to take into consideration as they develop and roll out circular economy action plans and roadmaps.

The African Union is also understood to be at an advanced stage of developing the circular economy roadmap which, once adopted, will guide implementation of similar roadmaps by member States.

Waste valorisation

Meanwhile, as Africa grapple with legacy waste and more volumes emanating from the prevailing linear economic models, experts are of the view that waste should be leveraged as a resource to make things like metals, energy production and waste water purification, among others.

Dr. Tobias Schmitz, for instance, indicates that negotiations were underway to deploy Basalia technology towards producing green energy out of municipal waste and purifying waste water in urban parts of West Africa’s Gambia and Senegal.

“In the case of Senegal, we are using that treat waste water to lift up aquifers and to generate irrigation across the city so that people can get jobs and produce vegetables for the city based on that irrigation from purified waste water,” he said.

He allayed concerns over the cost of such projects citing the fact that calculations found the cost to be 10 per cent below usual costs of waste-to-energy systems, and the return on investment is less than 10 years.

“The big difference is that there is zero emission from the system and all the waste are converted into marketable usable products. That means that we can finance most things from impact funds rather than asking the municipality or others who may have restricted budget to invest in something like this,” he says.